![]()

Introduction

The development of new fuel markets is a complicated process in which many aspects can slow market growth, such as:

- Incumbents protecting existing positions for fuel supply and distribution

- Customer perceived technology and operational performance risks

- Customers not willing to absorb the additional capital investments

- Absence of a fuel standard creates technical and commercial uncertainty across the value chain (fuel suppliers, customers and engine manufacturers)

- Gaps in regulations cause uncertainty about safety and environmental performance standards and potential compliance issues

- Uncertainty in relative fuel price development between new and existing fuels

- Commercial risk from being tied to a single or few suppliers and/or not yet commoditized market for the new fuel

- Early adopters are ‘penalized’ by higher initial capital and operational costs due to lack of scale and not yet materialised ‘learning curve effects’

- Lack of infrastructure that limits geographical reach to serve the market

- Uncertainty in payback timings and risk of stranded assets from investing too early

Among these, the dilemma of the ‘chicken and egg’ situation between initial lack of infrastructure and committed market size for the new fuel causes perhaps the biggest challenge in market development. Customers are unlikely to adopt a new fuel unless they are convinced it is backed up by sufficient infrastructure to provide flexibility, diversity, range, resilience and competition in fuel access. Suppliers are unwilling to invest in costly new fuel infrastructure unless they are convinced of a critical mass in early market size. This dilemma has been a very noticeable impediment in the development of LNG as transportation fuel.

Learnings from development of LNG as transportation fuel

The development of LNG as transportation fuel (see figure 1) has had a long gestation period. Maritime applications for LNG only recently appear to have overcome resistances in implementation. The ‘chicken-and-egg’ dilemma has certainly contributed to this slow initial growth. It has been a period of 20 years since the first LNG fueled ferry, the Glutra, was designed and subsequently built in 2000.

Figure 1: Development of LNG as Transportation fuel (IGU World LNG Report 2015, source Shell)

Many learnings can be drawn from the market development of LNG as maritime fuel, some of the headlines are:

- It was difficult to align the various industry parties with their own specific interests (ship owners and operators, oil & gas companies, classification societies, regulators, port authorities, etc.) under the shared ambition for establishing a safe, reliable and clean LNG as maritime fuel market. Independent consultants have been of service, helping to align interests and value propositions.

- For ship owners and operators, the economic costs for maintaining the existing ‘base case’ for ship fuels is continuously deteriorating under more stringent environmental regulations, see Figure 2.

- Competing fuels have seen a major shift in dynamics that has created new opportunities to hedge against divergent fuel price developments, including fuel-switching strategies. Decoupling of global oil and gas prices, as well as a convergence to lower global LNG prices has changed the competitive fuel market.

- Technology developments to make ships ‘LNG ready’ or able to run on multiple fuels have both lowered the upfront investment costs as well as improved operational flexibility.

- The early LNG as maritime fuel investment opportunities generated significant learning for global replication. For example, the experience gained contributed to the development of operational standards (hoses, couplings, procedures).

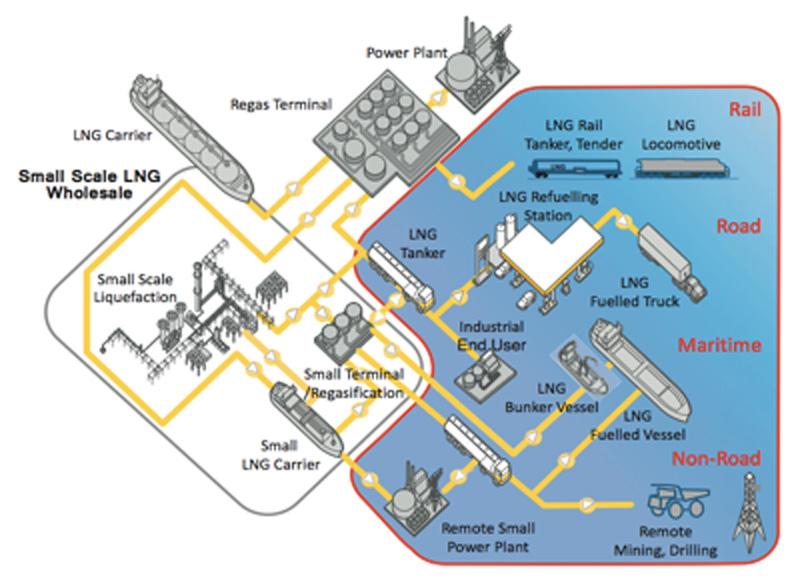

- Synergies in LNG infrastructure use and access by ‘anchor’ infrastructure has helped to seed markets for LNG as maritime fuel and has created critical mass for further growth.

Figure 2: The market development for LNG as maritime fuel was helped by increasingly greater impact of emission control regulations in the shipping sector, both by expansion of expansion of ECA and SECA as well as more stringent emission limits in these areas.

The latter learning point of anchor infrastructure in seeding opportunities for LNG as fuel can be further understood by the following two concrete examples:

Lithuania LNG

Lithuania has historically been a captive gas market for Gazprom, which at certain time periods caused it to pay the highest gas price in Europe. As a result of a strategic decision to reduce its physical and commercial dependence on Russian gas, Lithuania invested in the Klaipeda LNG import development using the FSRU ‘Independence’. Russia has scoffed this development as a disastrous investment as the FSRU utilization has remained very low. Lithuania however, hails the same development as a great success as it has been able to create enormous value for the country through lower Gazprom gas prices that are since just below LNG import parity. In addition, as a strategic infrastructure, the facility is ‘supposed’ to be underutilized to provide a strategic buffer against unexpected cuts in Russian gas supply. The availability of a strategic underutilized FSRU infrastructure in the Baltic captive shipping region then created the prospect of deploying this existing LNG infrastructure as a bunkering hub for LNG fueled vessels that are deployed in the Baltic, whilst maintaining its strategic role. As most of the LNG infrastructure costs have been sunk, this value proposition has been gaining significant momentum.

The specific learning in this example is the enabling role of the anchoring value proposition for the new fuel (strategic investment for physical and commercial leverage/flexibility). Additional new fuel market opportunities benefit physically and commercially as low cost bolt-on opportunities, such as LNG bunkering, LNG as maritime fuel and other small-scale LNG applications.

Singapore LNG

Singapore is for 96% dependent on natural gas supplies for its power generation. The country has no domestic energy sources and has been dependent on pipeline gas imports from Malaysia and Indonesia. These gas sources are now in decline and Singapore has established LNG import as replacement fuel to generate power. Singapore has taken the opportunity to diversify and expand on the LNG infrastructure to develop opportunities for strategic LNG storage (in case of global gas supply disruptions), LNG trading and LNG bunkering. Singapore is a strategic global maritime port and is a natural supply base for LNG as maritime fuel, not just serving the local South East Asia region, but also as a hub for the long-distance shipping lanes connecting the Far East region with Europe.

The specific learning in this example is the understanding of how the new fuel (LNG) has replaced a declining existing resource (pipeline gas) to fulfill future energy needs and how this infrastructure is further utilized with Singapore port’s activities and existing role as a commercial and strategic bunkering hub for a range of fuels (diversification).

What both these examples have in common is the development of an anchor position in infrastructure for fuel supply and/or storage for a key market need, followed by leveraging on this established infrastructure position by building new downstream market opportunities at lower costs.

Seeding market opportunities for hydrogen

The above learnings in developing LNG as a maritime fuel can potentially be replicated in seeding the market development for hydrogen:

- Spearhead a process for aligning various (cross-) industry parties with their own specific interests on the overall hydrogen value proposition

- Leverage on increasing ‘costs’ for maintaining the existing fuels (regulatory, environmental, political acceptance, etc.) to enhance the positioning of hydrogen (i.e. recognize that the ‘base case’ is not constant)

- Leverage on or create a major shift in dynamics between competing fuels that promotes hydrogen as a physical or commercial supply hedge

- Leverage on technology to lower investment costs and/or improve operational flexibility for the use of hydrogen.

- Create ‘anchor’ customer value propositions for hydrogen that justify the infrastructure development to establish hydrogen market presence.

- Seek synergies in the hydrogen infrastructure for seeding additional bolt-on new hydrogen market opportunities (diversification)

- Obtain operational experience from early hydrogen projects to demonstrate success and to provide specific input for the development of standards and procedures for global implementation.

Figure 3: The dilemma of the ‘chicken and egg’ situation between initial lack of infrastructure and committed market size causes perhaps the biggest challenge in market development of new fuels. Large scale industry applications can serve as anchors for subsequent more commoditized bolt-on market opportunities.

Anchor opportunities for hydrogen

The success for creating a hydrogen market is facilitated by the identification of tailored value propositions for specific anchoring applications. The seven learnings listed above provide some of the dimensions for scoping these anchor projects. It is expected that these seed applications will be highly tailored and specific. Project selection criteria should therefore not put much emphasis on the replicability of these unique circumstances to other potential projects. (Similarly, the investment rationale for the Lithuania LNG import project was highly unique in its circumstances. However, the bolt-on fuel opportunities that followed were more generic). The replicability is targeted in the bolt-on opportunities that follow.

Larger scale industrial applications are obvious targets for developing early hydrogen based value chains. For example, can excess wind-power capacity be captured as power-to-gas (hydrogen) offshore using obsolete oil & gas platforms and transported to refinery and chemicals complexes, utilising existing pipelines?

The hydrogen generation market is forecasted to grow from USD118 billion in 2016 to USD152 billion by 2021, growing at a CAGR of 5.2%. Also, hydrogen transportation is maturing: Air Products has built a 1.4 Bscfd hydrogen pipeline across the US Gulf Coast, supplied by over 20 hydrogen plants. Although forecasting the pace of hydrogen market development carries considerable uncertainty, timing would appear opportune to develop selected anchor growth positions in hydrogen in the next five-year period.

Conclusions

There are important learnings to be gained from progress made on LNG as maritime fuel to further develop hydrogen as fuel. The similarities not only focus on business development aspects, but hydrogen itself could well be a further addition to the existing suite of maritime fuels. As diversification of fuel sources and fuel applications appear to be accelerating and the hydrogen generation market is forecasted to grow with CAGR 5.2% to USD152 billion by 2021, timing would appear opportune to develop selected anchor positions in hydrogen during this next five-year period.